Relock 3.0: Relocation-based obfuscation revisited in Windows 11 on Arm¶

- Date: 2021/10/29

- Author: Koh M. Nakagawa

Introduction¶

My previous post introduced a new relocation entry for ARM64X: IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X, where I explained how this relocation entry allows ARM64X to behave as ARM64 and ARM64EC binaries.

Please refer to this post if you have not read it.

According to a tweet from a Microsoft developer, the ARM64X binary has been called a "chameleon binary" instead of a fat binary. ARM64X is a binary code that changes its architecture depending on its surroundings. Therefore, they named it chameleon, owing to its ability to change color to match its surroundings.

In my previous post, I explained that IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X has three relocation entries.

- Zero fill

- Assign value

- Delta

Of these, the relocation entry "assign value" is particularly interesting.

Unlike IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW, which is a well-known relocation entry, "assign value" allows arbitrary addresses to be overwritten with arbitrary values.

Because this "assign value" relocation entry enables flexible and dynamic binary rewriting, can it not be abused? This post describes an obfuscation technique that exploits IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X in ARM64X. In the following, IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X is referred to as DVRT ARM64X because this relocation entry is a Dynamic Value Relocation Table (DVRT) introduced in ARM64X.

Related works¶

Relocation-based obfuscation techniques have been known for a long time.

First, I will briefly explain the well-known base relocation entry (IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW) and the relocation-based obfuscation technique that exploits it.

Base relocation¶

First, let us briefly review the relocation process in Windows. In the recent version of Windows, ASLR has been enabled in most system modules; therefore, the value of the image base set at runtime is usually different from the value of BaseOfCode in the PE header. In this post, the value of BaseOfCode described in the PE header is denoted as "desired base" for clarity.

If the code is executed when the desired base is different from the image base, an error will occur in executing instructions specifying an absolute address.

For example, consider the following code that prints a string in the .data section for standard output.

push 0x403018 # a pointer to a string

push 0x402100 # "%s\n"

call _printf # printf("%s\n", "Hello")

As shown above, the data contained in the .data section is specified as an absolute address (such as 0x403018 and 0x402100).

This absolute address is for the case where the image base is set to the desired base (0x400000).

Therefore, unintended data access will occur when the image base is different from the desired base owing to ASLR.

A program loader solves this problem by dynamically patching the executable at runtime to work on the new image base, which is called the relocation process.

The following pseudo-code illustrates how the relocation is applied.

// Listing 1

// The following pseudo code is from https://media.defcon.org/DEF%20CON%2026/DEF%20CON%2026%20presentations/DEFCON-26-Nick-Cano-Relocation-Bonus-Attacking-the-Win-Loader.pdf

auto delta = imageBase - desiredBase;

for (auto reloc : relocs) {

auto block = (base + reloc.VirtualAddress);

for ( auto entry : reloc.entries) {

auto adr = block + entry.offset;

// apply patch to the image

if (entry.type == IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW)

*((uint32_t *)adr) += delta;

else if (entry.type == IMAGE_REL_BASED_DIR64)

*((uint64_t *)adr) += delta;

else if (entry.type == IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGH)

*((uint16_t *)adr) += (uint16_t)((delta >> 16) & 0xFFFF);

else if (entry.type == IMAGE_REL_BASED_LOW)

*((uint16_t *)adr) += (uint16_t)delta;

}

}

In the relocation process, delta (the subtraction of the desired base from the image base) value is added to the instruction operand containing the absolute address. After the relocation process, the absolute addresses are fixed to work in the new image base.

There are several types of relocations (IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW, IMAGE_REL_BASED_DIR64, IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGH, and IMAGE_REL_BASED_LOW), and patches differ depending on the relocation type. Some relocations are disabled in recent Windows (for example, IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGH is no longer supported).

Next, I introduce the previous studies of relocation-based obfuscation.

"Relock-based vulnerability in Windows 7" (Virus Bulletin 2011)¶

This research explains relocation-based obfuscation in Windows XP/2000 and Windows 7.

The idea is simple; we can extract the payload at runtime by exploiting the relocation process as a decoder.

So, we can encrypt the data in the executable file (e.g., code in the .text section), then extract the payload at runtime by the dynamic patch of the relocation process.

As can be seen from the code above (Listing 1), when the relocation process is used as a decoder, the ability to control the value of delta is essential.

In this research, the authors use the vulnerability in the Windows loader to control the delta value.

Specifically, the following two vulnerabilities were used:

- Windows XP/2000: When the desired base is set to 0, the image base at runtime is automatically set to 0x10000.

- Windows 7: When the desired base is set to 0X7FFE0000 or higher, the runtime image base is automatically set to 0x10000.

For Windows XP/2000, a method was proposed to exploit the IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGH.

This obfuscation technique was used to obfuscate the W32/Relock malware.

However, IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGH is no longer available on Windows 7.

Instead, a method using IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW has been proposed, and this method is called Relock 2.0 in their research article.

"Relocation Bonus Attacking the Windows Loader Makes Analysts Switch Careers" (DEF CON 26)¶

This presentation describes the relocation-based obfuscation available in Windows 7 and Windows 10.

The method used for Windows 7 is the same as that described in the previous section.

This presentation is novel in that it proposes a new method for Windows 10.

Since the vulnerability described in the previous section was fixed in Windows 10, the delta could no longer be controlled.

The author solved this problem by repeating the execution until the image base value becomes a specific value.

Relocation-based obfuscation by DVRT ARM64X¶

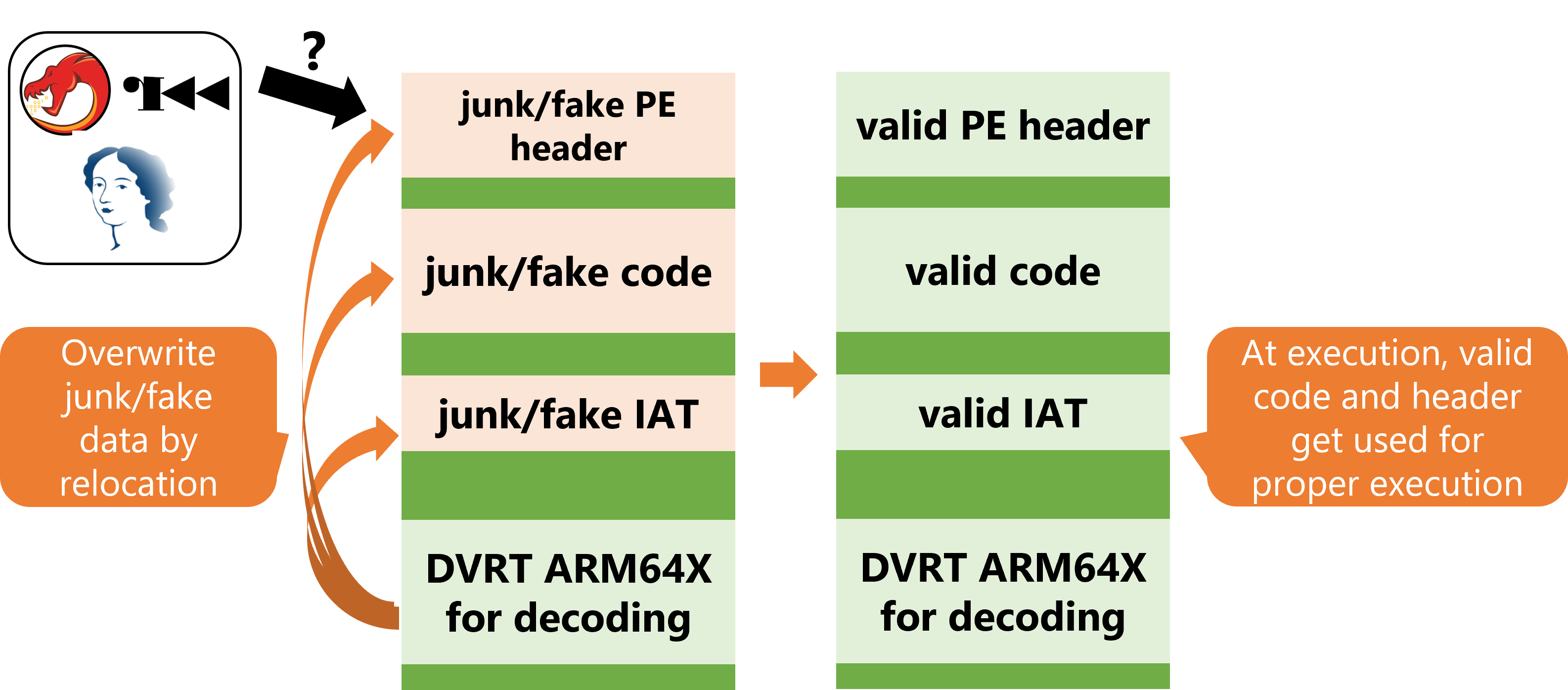

As mentioned in the introduction, the DVRT ARM64X relocation enables an arbitrary write in the target module. By abusing DVRT ARM64X, we can obfuscate an executable in the same manner as described in the previous section (Figure 1).

Let me show an example to obfuscate some code in .text using DVRT ARM64X.

An executable demonstrated in this section can be created using this tool.

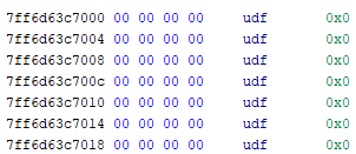

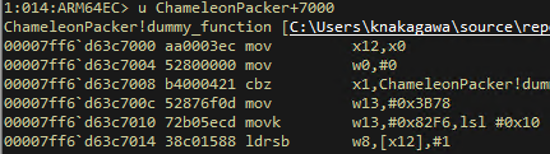

Figure 2 shows the contents of the obfuscated executable's code section. The junk data are placed in the code section (Figure 2).

Of course, this code cannot be executed in its current form. So, we need to overwrite the code section with a dynamic patch using "assign value" relocation of DVRT ARM64X. By adding the "assign value" relocation entries of DVRT ARM64X and exploiting these dynamic patches, we can expand the following code and execute it at runtime (Figure 3).

Additionally, by changing the PE Header's contents, it is possible to change the contents of the IAT and EAT to something else. This makes it possible to cheat the results of the static analysis tools.

In contrast to the previous studies described in related works, we can not only change the contents of IATs and EATs to junk data but also change them and display fake IATs and EATs. Remember that the DVRT ARM64X is different from conventional relocation entries in that it can enable the arbitrary write in the target module. Therefore, it is possible to make the file appear to be an unobfuscated executable.

Further techniques to make analysis more difficult¶

You might think that this obfuscation technique can be easily analyzed by dumping the executable on the memory. Is it possible to make the analysis even more difficult? In the following section, I introduce some ideas to make the analysis more difficult.

Section Header Modification¶

The result of the memory dump is usually analyzed by a disassembler such as Ghidra. A disassembler determines where to map each section from the PE Section Header.

What will happen if a part of this section header is NULL?

Consider the following program. Compile it and save it as "TestSectionHeader.exe."

// Listing 2

// Compile and save as "TestSectionHeader.exe"

#include <iostream>

#pragma code_seg(".sect1")

void hoge() {

std::puts("hoge");

}

int main() {

hoge();

}

In the above source code, #pragma code_seg(".sect1") is added.

This pragma creates a new code section called .sect1 in addition to the default .text section (Figure 4).

The code for the hoge function and the main function are placed in .sect1.

Next, edit the image section header in Ghidra and set most of the fields in the entry corresponding to .sect1 to NULL (Figure 5).

Then, reopen the same executable and you will see the following.

You can see that .sect1 is not listed in the Program Tree.

By using this property and setting the RVA of the section header to be hidden by DVRT ARM64X to NULL at runtime, we can make its analysis difficult after the memory dump. The value of RVA can also be specified in another section as its value. This makes analysis difficult because the contents of another section are displayed when it is opened with a disassembler.

Fooling WinDbg¶

Next, I introduce a method to make it difficult to analyze extracted code with WinDbg. Before explaining this, let me explain the Hybrid Code Map.

Recall that ARM64X contains the code for three architectures: ARM64, ARM64EC, and x64. Hybrid Code Map is a structure that manages the location of an architecture's code in the addresses. The following is the result of outputting the contents of the Hybrid Code Map using dumpbin.

> dumpbin /LOADCONFIG KernelBase.dll

...

Hybrid Code Address Range Table

Address Range

----------------------

x64 0000000180001000 - 000000018000835F (00001000 - 0000835F)

arm64 0000000180009000 - 00000001801111CB (00009000 - 001111CB)

arm64ec 0000000180112000 - 0000000180227117 (00112000 - 00227117)

x64 0000000180228000 - 000000018022A001 (00228000 - 0022A001)

If the process is ARM64EC, the area marked as x64 and ARM64EC in the Hybrid Code Map is executed, and the area marked as ARM64 is not used. WinDbg changes the machine architecture in the disassembly view depending on which code (x64 or ARM64EC) is executed. WinDbg probably uses the Hybrid Code Map information to determine the machine architecture.

Now, the ARM64EC process does not execute ARM64 code in ARM64X, but what would happen if we moved the program counter the ARM64 code in ARM64X? We can observe an interesting behavior.

Look at the gif above. b instruction makes a transition to the code in the area marked as ARM64.

After the transition, the disassembly result is ???, indicating that it could not be correctly disassembled.

However, we can observe that the step execution can be continued!

The code at the destination address of the b is actually the shellcode of x64 calling MessageBoxA as shown below.

0x00000000 33c0 xor eax, eax

0x00000002 4c8bca mov r9, rdx

0x00000005 4c8bd1 mov r10, rcx

0x00000008 4885d2 test rdx, rdx

0x0000000b 0f8491000000 je 0xa2

0x00000011 450fb602 movzx r8d, byte [r10]

0x00000015 4d8d5201 lea r10, [r10 + 1]

0x00000019 4183c820 or r8d, 0x20

0x0000001d 4133c0 xor eax, r8d

0x00000020 8bd0 mov edx, eax

0x00000022 d1e8 shr eax, 1

0x00000024 83e201 and edx, 1

0x00000027 69ca783bf682 imul ecx, edx, 0x82f63b78

0x0000002d 33c8 xor ecx, eax

0x0000002f 8bc1 mov eax, ecx

0x00000031 d1e9 shr ecx, 1

0x00000033 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000036 69d0783bf682 imul edx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x0000003c 33d1 xor edx, ecx

0x0000003e 8bc2 mov eax, edx

0x00000040 d1ea shr edx, 1

0x00000042 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000045 69c8783bf682 imul ecx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x0000004b 33ca xor ecx, edx

0x0000004d 8bc1 mov eax, ecx

0x0000004f d1e9 shr ecx, 1

0x00000051 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000054 69d0783bf682 imul edx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x0000005a 33d1 xor edx, ecx

0x0000005c 8bc2 mov eax, edx

0x0000005e d1ea shr edx, 1

0x00000060 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000063 69c8783bf682 imul ecx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x00000069 33ca xor ecx, edx

0x0000006b 8bc1 mov eax, ecx

0x0000006d d1e9 shr ecx, 1

0x0000006f 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000072 69d0783bf682 imul edx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x00000078 33d1 xor edx, ecx

0x0000007a 8bc2 mov eax, edx

0x0000007c d1ea shr edx, 1

0x0000007e 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000081 69c8783bf682 imul ecx, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x00000087 33ca xor ecx, edx

0x00000089 8bc1 mov eax, ecx

0x0000008b d1e9 shr ecx, 1

0x0000008d 83e001 and eax, 1

0x00000090 69c0783bf682 imul eax, eax, 0x82f63b78

0x00000096 33c1 xor eax, ecx

0x00000098 4983e901 sub r9, 1

0x0000009c 0f856fffffff jne 0x11

0x000000a2 c3 ret

Although the exact cause is unknown, the ARM64 code regions are interpreted and executed as x64 code in the ARM64EC process. However, WinDbg refers to the Hybrid Code Map and disassembles as ARM64. Therefore, although the code can be executed, the disassembly view will be invalid.

Side Effect: Parent-process-dependent code execution¶

Finally, I would like to mention the side effect of the DVRT ARM64X relocation-based obfuscation.

Recall that DVRT ARM64X relocation is only applied when ARM64X is executed as an ARM64EC or x64 process. The relocation is not applied if it is run as an ARM64 process.

For ARM64X DLLs, DVRT ARM64X is applied when ARM64EC or x64 processes use them. However, what about ARM64X EXEs? Longhorn examined this, and the following table summarizes the results obtained by him. For ARM64X EXEs, the executed code in ARM64X depends on the parent process that runs it.

| Architecture of parent process | Architecture of executed code |

|---|---|

| x86 | ARM64 |

| x64 | ARM64EC |

| ARM64 | ARM64 |

| ARM64EC | ARM64EC |

DVRT ARM64X relocation is applied only when the parent process architecture is ARM64EC or x64. This means that if the parent process architecture is x86 or ARM64, DVRT ARM64X relocation is not applied, and the ARM64 code in ARM64X is executed. Thus, ARM64X is a binary with different execution results depending on the architecture from which the parent process runs.

This property can be exploited by attackers.

For example, let us consider analyzing the ARM64X binary in a sandbox environment.

ARM64X PE appears to be ARM64 PE through a simple static analysis (e.g., file type check by UNIX file command).

Therefore, if you do not identify ARM64X, you might run it as an ARM64 PE and obtain the result of the dynamic analysis (despite the fact that ARM64EC actually contains malicious code!).

When scrutinizing the results of dynamic analysis, it is necessary to check not only to look the results when running as an ARM64 but also the results when running as an ARM64EC.

Conclusion¶

In this article, we proposed the relocation-based obfuscation technique using DVRT ARM64X.

As explained, relocation-based obfuscation techniques have been known for a long time. However, these techniques are now almost unusable because they rely on the image loader vulnerabilities that are currently fixed. With the introduction of DVRT ARM64X in Windows on ARM, relocation-based obfuscation can be used again for practical use. Since this technique does not rely on the vulnerabilities of the image loader, the proposed method can be used in Windows on ARM for a long time.

I have also presented ideas to make the analysis of ARM64X more complicated and a side effect of the dependency of execution results on the parent process. Although some of these are not directly related to relocation-based obfuscation, they can be combined with the DVRT ARM64X obfuscation method to make analysis more difficult.

Microsoft has not yet officially documented ARM64X, and there are not many reverse engineering results. Further research is required in this regard.