Discovering a new relocation entry of ARM64X in recent Windows 10 on Arm¶

- date: 2021/07/13

- author: Koh M. Nakagawa

Introduction¶

Last December, Microsoft announced the x64 emulation for Windows 10 on Arm. This is excellent news for Windows 10 on Arm users because some applications are distributed as 64-bit-only x64 binaries. Now, they can use x64 apps with this x64 emulation feature.

This news is exciting for me because I'm curious about the emulation technologies of Windows.

Last year, at Black Hat EU 2020, I presented a new code injection technique in Windows 10 on Arm.

During this research, I analyzed various binaries for x86 emulation (xtajit.dll and xtac.exe) and investigated how emulation works and some techniques used for speeding up x86 emulation (binary translation cache files and CHPE *).

So, it was natural for me to examine the internals of the x64 emulation.

* CHPE is a PE file containing both Arm64 and x86 code. This will be explained in more detail later.

Digging into the x64 emulation, I discovered a new type of CHPE called CHPEV2 ARM64X. This CHPE has an intriguing property that it can be used by both x64 emulation processes and Arm64 native processes. Typically, the machine type in a DLL must match the architecture of the process loading it. If there is a mismatch, the DLL will not be loaded correctly. However, in CHPEV2 ARM64X, it can be loaded from both x64 emulation processes and Arm64 native processes! What makes it possible?

To uncover this, I analyzed the CHPEV2 parser logic in the Windows kernel and found that a new relocation entry, IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X makes this possible.

This article explains the IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X and how it makes CHPEV2 binaries loaded from both x64 and Arm64 processes.

Compiled Hybrid PE (CHPE)¶

First, let me explain CHPE to those of you who are unfamiliar with it.

CHPE is a new type of PE file containing both x86 and Arm64 code for improving the performance of x86 emulation in Windows 10 on Arm.

It looks like an x86 PE, that is, the machine type in IMAGE_NT_HEADERS of this PE is x86.

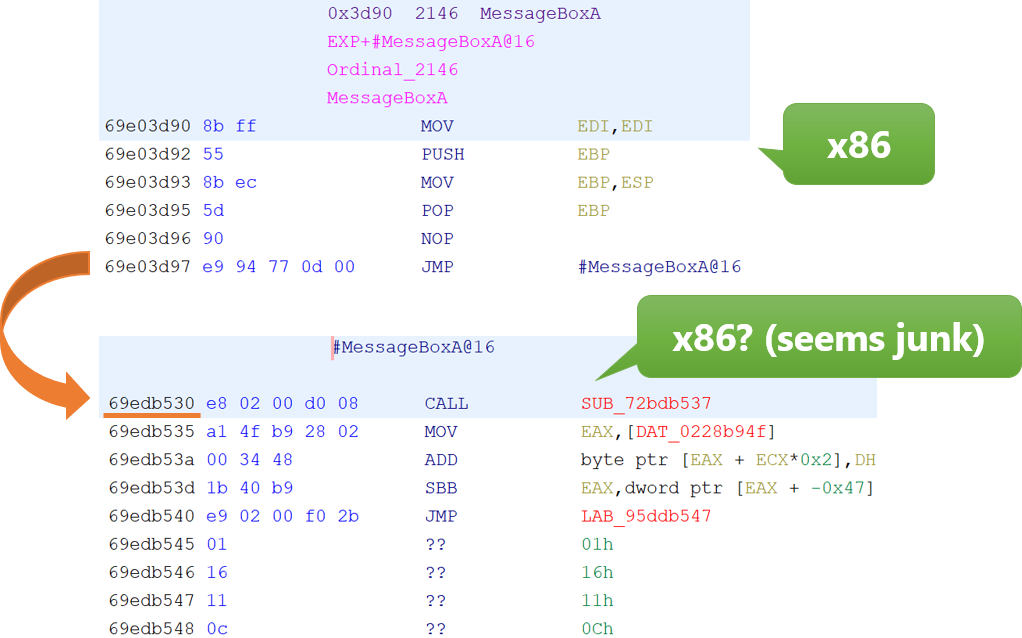

When you disassemble an exported function, you will find x86 instruction sequences.

However, following the instruction sequences, you will encounter the junk code block (see assembly instructions from 69edb530 in Figure 1).

MessageBoxA function.This junk code is actually Arm64 code (Figure 2).

0x69edb530 by specifying Arm64 as the architecture.The purpose of this PE format is to reduce the amount of JIT translation. Typically, a function of an x86 PE is executed after translating the entire function to Arm64 code. However, in CHPE, only the function's prologue needs to be translated because the function body has already been translated.

Why do prologues of functions exist as x86 code? As pointed out in the blog post, it is likely to maintain the backward compatibility of some applications using inline hooking. These applications modify the prologues of functions to inspect the argument values.

Currently, Windows 10 on Arm provides some of the System DLLs as CHPEs, which are in the directory %SystemRoot%\SysChpe32.

Some Microsoft Office binaries are also distributed as CHPEs.

CHPEV2¶

One of the significant changes after the introduction of x64 emulation is that most DLLs previously built as Arm64 (e.g., DLLs in %SystemRoot%\System32) are now CHPE.

This script can be used to determine which of the system DLLs are CHPEs.

In the following, I will refer to the new CHPE as CHPEV2 * (and the one in the previous section as simply CHPE).

* I named "CHPEV2" from the string "CHPEV2" in the Windows Insider SDK header (

ksarm64.h).

CHPEV2 differs from the CHPE introduced in the previous section, based on the following points:

- It contains both x64 and Arm64 code (CHPE contains both x86 and Arm64 code).

- There are two types of CHPEV2: one has the Arm64 machine type, and the other has the x64 machine type in

IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64.- CHPEV2 having the x64 machine type is called ARM64EC.

- CHPEV2 having the Arm64 architecture is called ARM64X.

- CHPEV2 ARM64EC is only used by x64 emulation processes.

- "EC" possibly stands for "Emulation Compatible."

- Some system EXEs, such as

PowerShell.exe,mmc.exeare CHPEV2 ARM64EC.

- CHPEV2 ARM64X is used by both x64 emulation processes and Arm64 native processes.

- It is a fat binary containing code for x64 emulation processes and code for Arm64 native processes.

- "ARM64X is the resulting binary from linking ARM64 and ARM64EC objs and libs into one."

- Much of the system DLLs under

%SystemRoot%\System32and some EXEs, such ascmd.exe, are CHPEV2 ARM64X.

CHPEV2 ARM64EC is the x64 version of CHPE (i.e., it looks like an x64 PE but contains both x64 and Arm64 code), so is not-so-new.

However, the CHPEV2 ARM64X is different. Of particular interest (as I said), CHPEV2 ARM64X DLLs can be loaded from x64 emulation processes, although they contain the Arm64 machine type.

Typically, when the machine type in the loaded DLL is different from the architecture of the process, it will not be loaded correctly. However, in the case of the CHPEV2 built for ARM64X, these DLLs are loaded correctly.

Moreover, we can find such strange behavior when we obtain the exported API addresses. For example, consider the following code.

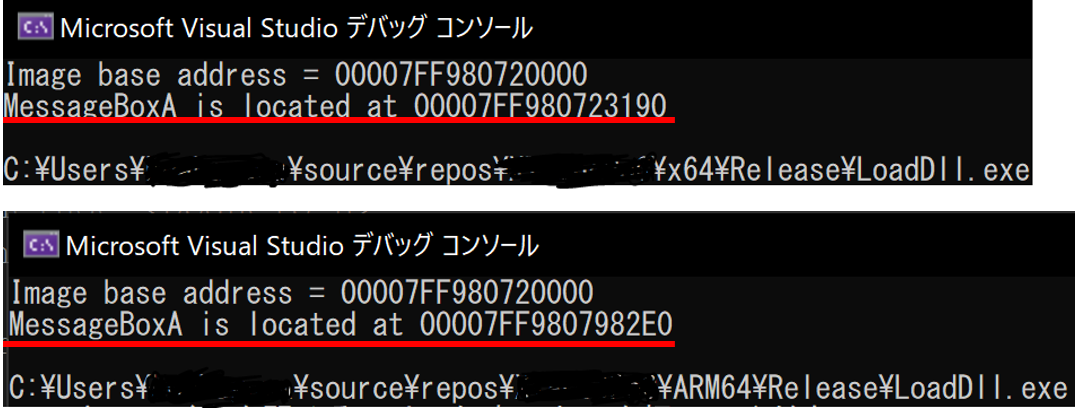

When building this source code by specifying x64 and Arm64 as the build targets and executing these EXE files, we obtain the following output (Figure 3).

The exported address differs between the execution by the x64 emulation process and the execution by the Arm64 native process.

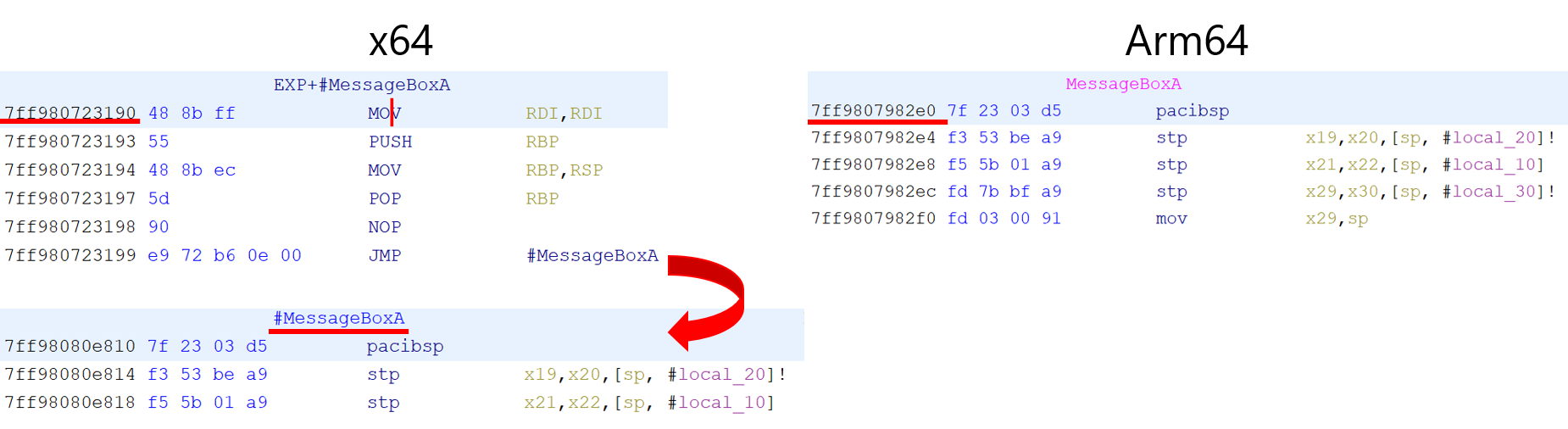

Analyzing this user32.dll statically, we can find two MessageBoxA functions (#MessageBoxA for x64 and MessageBoxA for Arm64), as shown in Figure 4.

#MessageBoxA function called by the x64 emulation process (left) and the MessageBoxA function called by the Arm64 native process (right).This CHPEV2 ARM64X binary appears to change its machine type and export functions according to the architecture information of the process that uses it.

What makes these possible?

The answer to the question is the existence of a dynamic patch by a new relocation entry called IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X.

New Dynamic Value Relocation Table (DVRT): IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X¶

IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X exists following the base relocation block in the .reloc section and has been added as a new type of Dynamic Value Relocation Table (DVRT) *.

This relocation entry is applied from the kernel side by calling nt!MiApplyConditionalFixups.

When the patch is applied, various information such as architecture information and an offset of Export Address Table (EAT) are overwritten at runtime.

* DVRT is a relocation entry introduced to apply mitigation techniques such as Return Flow Guard (RFG) and retpoline at runtime. It overwrites a part of the code area at runtime to enable these mitigation techniques. For more details, see Tencent Security Xuanwu Lab blog post and Microsoft blog post.

Now let's look at the data structure of IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X.

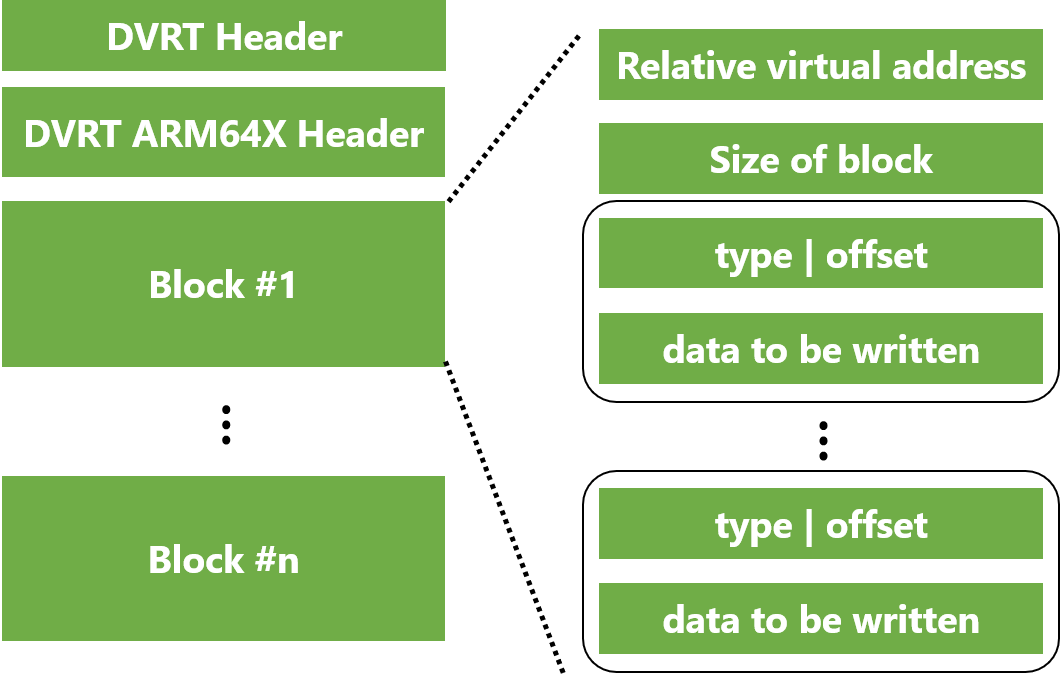

Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram of the IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X data structure.

IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X First, the DVRT header (IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_TABLE) is followed by the header of the IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X table (called IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X_HEADER).

The table consists of several blocks specified by the IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X_BLOCK structure.

There is one block per page to which the relocation is applied, and the VirtualAddress of IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X_BLOCK contains the page RVA.

The member Entries is an array whose element size is variable (the size of each element is at least two bytes).

The first two bytes of data of each component is represented by the following MetadataAndOffset structure, where the offset is an offset from the starting address specified in the page RVA for the block, and meta contains the relocation type and other metadata (sign or scale index).

The lower two bits of meta specify the relocation type.

There are three types of relocations.

Next, I will explain the data structure for each relocation type.

Relocation type 1: zero fill (meta & 0b11 == 0b00)

This entry is used to clear the data at the target address to zero.

The size is 2^x bytes, where x is the upper two bits of meta.

The following C code illustrates how this relocation entry is applied.

Relocation type 2: assign value (meta & 0b11 == 0b01)

This entry is used to overwrite the data in the target address with a specified value.

The size to be written is encoded in meta in the same manner as for "zero fill".

In this relocation entry, MetadataAndOffset is followed by data whose size is 2^x bytes, and this data is overwritten to the target address.

The following pseudocode illustrates how this relocation entry is applied.

Relocation type 3: add (or sub) delta (meta & 0b11 == 0b10)

This is an entry to add (or subtract) an offset in multiples of four (or eight) to the data in the target address.

The scale factor and offset sign are encoded in the upper two bits of the meta, as shown below.

| meta[3] (scale) | meta[2] (sign) |

|---|---|

| 8 (for 1) 4 (for 0) | minus (for 1) plus (for 0) |

In this relocation entry, MetadataAndOffset is followed by two bytes of data.

This value multiplied by the scale factor is added (or subtracted) to the data in the target address.

Example: user32.dll¶

Let's look at what data are overwritten after relocations of IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X are applied.

Here, I take user32.dll as an example of CHPEV2 ARM64X.

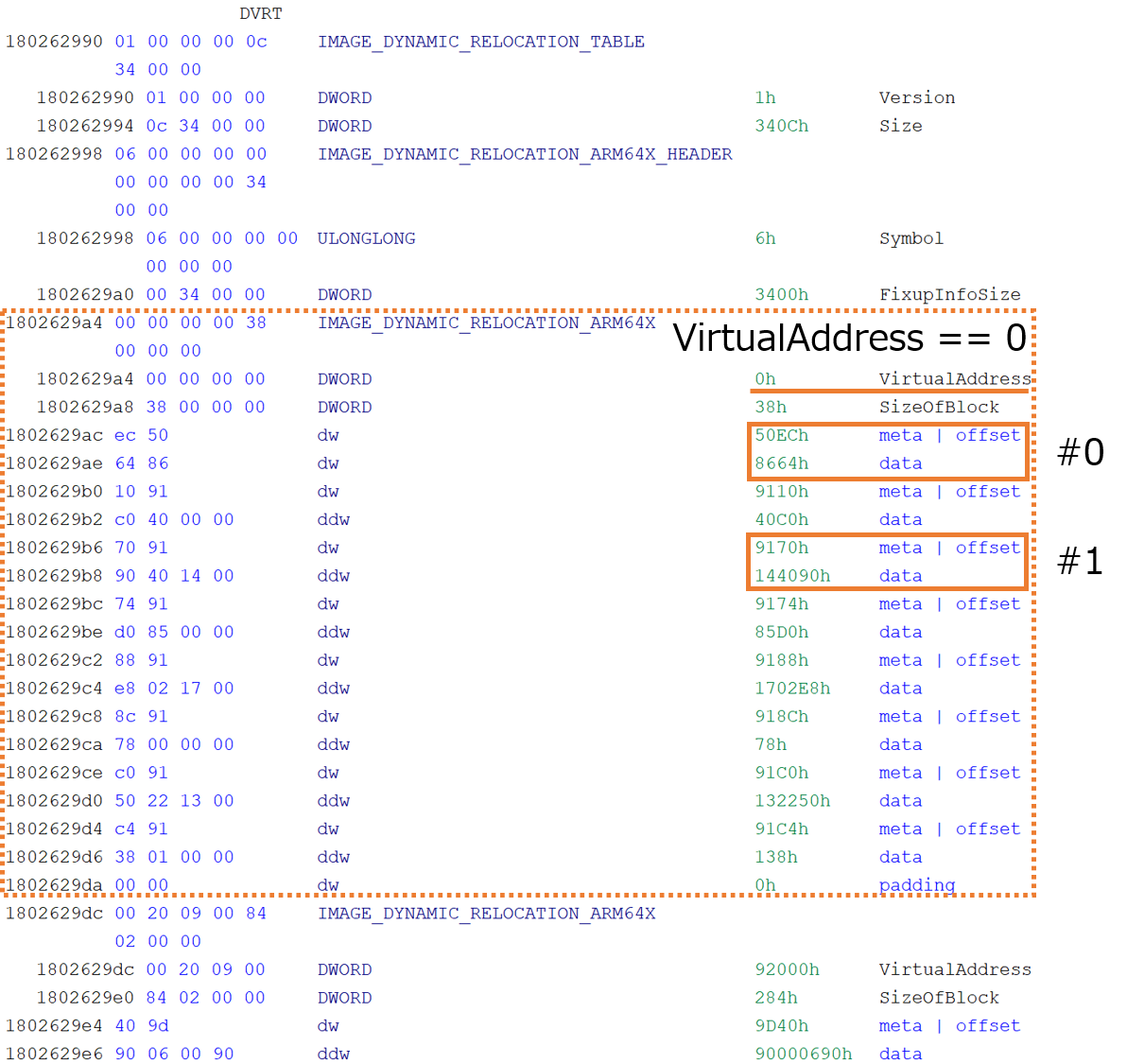

The DVRT of the user32.dll is shown in Figure 6.

This figure shows only the block whose VirtualAddress value is 0 in IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X.

IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X of user32.dll The first record (marked #0 in Figure 6) has a meta | offset value of 0x50ec (meta is 0x5 and offset is 0xec).

According to the value of meta, the type of this relocation is "assign value" (the lower two bits are 0b01), and its size is two bytes (upper two bits are 0b01).

Therefore, this relocation entry means that the data at 0x1800000ec (where the image base is 0x180000000) is overwritten with 0x8664.

Now, when you look at 0x1800000ec, you can find that it points to the IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64.IMAGE_FILE_HEADER.Machine (Figure 7).

user32.dll Hence, after the dynamic patch of this relocation entry is applied, the machine type in IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64 is changed from AArch64 (0xaa64) to x86_64 (0x8664).

This is why the same DLL can be used by both the x64 emulation process and the Arm64 native process. When ARM64X binaries are loaded by x64 emulation processes, the machine type is dynamically written by this relocation entry, so there is no mismatch in the architecture information.

Next, I will explain why the address of the EAT entry looks different between the x64 and Arm64 processes.

Let's look at entry #1 in Figure 6.

By Interpreting the relocation entry in the same manner as #0, we find that the four bytes of the data at address 0x180000170 will be overwritten with 0x144090.

When you look at the code at 0x180000170, you find that it points to the VirtualAddress of IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT (Figure 8).

user32.dll So, after the dynamic patch of this relocation entry is applied, the VirtualAddress value is overwritten with 0x144090.

Let's look at the data at 0x144090 from the image base address (0x180000000).

Another EAT can be found here (Figure 9).

Thus, CHPEV2 ARM64X has two EATs for the x64 and Arm64 processes.

user32.dllThese two entries are switched depending on whether or not this relocation entry is applied. That's why CHPEV2 ARM64X changes its behavior depending on the architectures of processes using them.

Visual Studio 2019 support of CHPEV2¶

There is no build tool available for CHPE, but Microsoft's internal MSVC allows it to be specified as a target.

On the contrary, the build tool for CHPEV2 has been released to the public according to the release notes of Visual Studio 2019.

So, you can build your own ARM64EC and ARM64X binaries using the latest version of Visual Studio 2019.

Conclusion¶

In this article, I have explained what CHPEV2 is and a new relocation entry, IMAGE_DYNAMIC_RELOCATION_ARM64X in CHPEV2 ARM64X.

We saw that the dynamic patch by this relocation entry makes it possible for CHPEV2 ARM64X to be used by both the x64 emulation processes and native Arm64 processes.

CHPEV2 has many other interesting properties (such as a64xrm section, IAT Fast Forwarding, and Auxiliary IAT), which are not covered in this post. I'll cover these topics in future posts.

Tools for analyzing ARM64X binaries are available in this repository. Please check it out.

Additional notes¶

Very recently, Microsoft officially announced CHPEV2 ARM64EC in their blog post. Details of CHPEV2 ARM64X are not included, but I think that its details might be announced soon.