Reverse-engineering Rosetta 2 part1: Analyzing AOT files and the Rosetta 2 runtime¶

date: 2021/2/19

author: Koh M. Nakagawa

Introduction¶

Apple announced that it would be moving from Intel processors to Arm-based Apple Silicon CPUs for Macs at WWDC 2020. The Apple Silicon-based Mac Book Air and Pro were released in October 2020 with great fanfare.

One of the issues that arise with the CPU transition is application compatibility. Since Apple Silicon is an Arm-based processor, applications built for Intel-based Macs will no longer work. To solve this problem, Apple offers the following two technologies:

- Universal Binary 2

- Rosetta 2

Universal Binary 2 is a mechanism to encapsulate binaries built for multiple architectures into a single binary, which is also called Fat Binary. Apple has been using this technology for a long time to maintain backward compatibility. A Mach-O loader selects the binary with the best architecture for the machine it is running on, then loads only that binary into memory to run the program. Most macOS Big Sur system binaries are currently Fat Binaries, containing binaries built for both Arm and Intel architectures.

Rosetta 2 is a technology that translates Intel-based binaries or JIT-generated code into Arm-based binaries or code. It is the successor to Rosetta, which was also used in the past processor transition. There is not much information officially released by Apple. Of course, there is no source code available, unlike the XNU kernel. Also, at the time of writing this article, there seems to be no article that examines it in detail.

In this article, I introduce some reverse engineering results of Rosetta 2.

Why I take a closer look at Rosetta 2?

The reason is that I'm interested in translated binaries in Rosetta 2 and examining the possibility of exploiting them. I presented a new code injection technique in Windows 10 on Arm at Black Hat EU last December. The code injection is achieved by modifying x86 to Arm (XTA) binary translation cache files. This research encourages me to examine whether similar code injection techniques can be achieved with Rosetta 2.

In this part, I will cover the following points:

- The executables associated with Rosetta 2 and their roles

- Analysis results of the translated binaries

- JIT binary translation capabilities of Rosetta 2 (mainly focusing on x86_64 machine code decoding process)

In the following, I will follow Apple's terminology when referring to architecture.

- arm64: The architecture specified when generating binaries to run on an Apple Silicon Mac

- x86_64: The architecture specified when generating binaries to run on an Intel-based Mac

Setting up the analysis environment¶

First, I show you how to set up the analysis environment.

Rosetta 2 is not installed by default on an Apple Silicon Mac. So, you need to install it following the pop-up that appears when you run an x86_64 code for the first time.

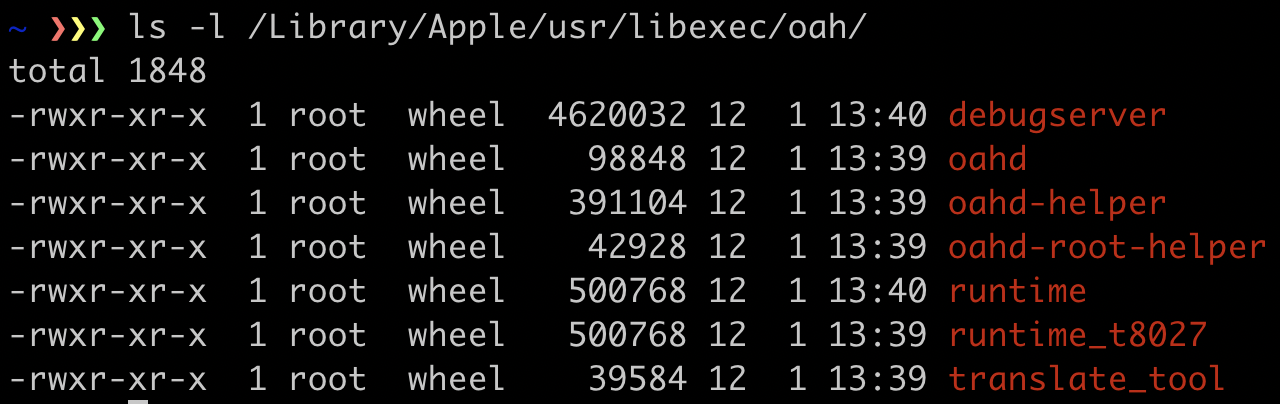

After the installation, a folder named /Library/Apple/usr/libexec/oah/ (hereinafter referred to as the oah folder) is created, and you can see the following binaries installed.

The role of each binary will be explained later.

The next step is to disable System Integrity Protection (SIP). This is because the folder that contains the translated binaries is protected by SIP and cannot be accessed by default even with administrative privileges.

Please follow the steps below to disable SIP.

- Restart the OS

- Press and hold Touch ID to boot in the recovery mode

- Select Terminal from "Utilities" at the top of the screen

- Type

csrutil disableand execute - Restart the OS again

In addition to this, please install Xcode and Command Line Tools for Xcode to use Clang and LLDB.

Roles of oahd and oahd-helper¶

First, let's create a command line application built for x86_64 and monitor system events (e.g., process creation, file-system activities, and memory mapping) when the x86_64 application runs.

$ cat hello.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

puts("Hello World");

return 0;

}

$ clang -arch x86_64 hello.c -o hello.out # specify x86_64 as the target architecture

$ file hello.out

hello.out: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

To obtain several system events, I used EventMonitor created using the Endpoint Security Framework. I will release EventMonitor as an OSS soon.

Start EventMonitor and run hello.out.

The following jsonl file contains logs obtained by EventMonitor. The only events related to Rosetta 2 are extracted.

When you look at the first line of the logs, you can see an event where /bin/zsh executes hello.out.

{"event":{"log":{"args":[".\/hello.out"],"cwd":{"path":"\/Users\/konakagawa.ffri","path_truncated":false},"last_fd":4,"target":{"executable_path":"\/Users\/konakagawa.ffri\/hello.out","group_id":54132,"pid":54132,"ppid":48492,"session_id":48491}},"type":"exec"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/bin\/zsh","group_id":54132,"pid":54132,"ppid":48492,"session_id":48491}}

After the exec system call, oahd daemon checks for the file /var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0/hello.out.aot.

... (the oahd checks for the AOT file)

{"event":{"log":{"relative_target":"var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot","source_dir":{"path":"\/","path_truncated":false}},"type":"lookup"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":426,"ppid":1,"session_id":426}}

The file with the extension .aot contains the result of the translation from x86_64 to arm64.

We refer to this file as the AOT file.

The name .aot comes from Ahead-Of-Time, which means that the translation is performed before a thread actually starts.

The oahd is the management daemon for the AOT files.

Since this is the first time we run hello.out, the oahd cannot find the corresponding AOT file. So, it creates a new AOT file.

If the same binary in the same path has already been executed and the AOT file has been created, the oahd uses it.

You can see the folder named /var/db/oah in the above logs.

This folder has a Oah.version file at the top, which is supposed to contain the version information for Rosetta 2.

Also, this folder has 16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00 folder.

We can see that multiple folders are containing AOT files in it.

The names of these folders are SHA-256 hash values that are calculated from both the contents of the file in x86_64 code and the path where it was executed.

# /var/db/oah contains the Oah.version file and 16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00 folder

$ ls -l /var/db/oah

total 8

drwxr-xr-x 6528 _oahd _oahd 208896 2 13 22:22 16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00

-rw------- 1 _oahd _oahd 32 1 27 14:44 Oah.version

# show some AOT files

$ ls -l /var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/* | head -n 10

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/00088a4116103832383ae2866e61d745d3d0013c5073ed032dabf6a785611db9:

total 40

-rwxr-xr-x 1 _oahd _oahd 17656 1 27 14:45 FlashlightModule.aot

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/0008a5059fda4b8aee7110b04a3e65f175a80ea55a64129a7660c7d3ed77a9d5:

total 56

-rwxr-xr-x 1 _oahd _oahd 25928 1 27 14:47 libswiftAccelerate.dylib.aot

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/00091f4ca51a770fa7a398f4320efe920fa8c3fc611247dcf55ca025f22301d4:

total 600

-rwxr-xr-x 1 _oahd _oahd 304536 1 27 14:45 AirPlayRoutePrediction.aot

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/000a1ab017d7e24b25cd58739ae01120b8a6d3a9cff37235156dced0123f2c3c:

total 24

-rwxr-xr-x 1 _oahd _oahd 12280 1 27 14:46 NanoNewsComplications.aot

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/001dac33f82e558695268fb4a4285f47e9806766e7398e377d9dff59235399f5:

total 1192

-rwxr-xr-x 1 _oahd _oahd 606347 1 27 14:46 TSCoreSOS.aot

Note that the folders and files under /var/db/oah are protected by SIP, so we cannot access even with admin privileges.

After disabling SIP, we can access these folders and files with admin privileges.

Now, back to the analysis of the logs.

oahd checks for the AOT file, and if not found, it runs oahd-helper to create a new AOT file.

... (oahd creates hello.out.aot.in_progress file)

{"event":{"log":{"dest_path":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false},"dest_type":0,"filename":null},"type":"create"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":426,"ppid":1,"session_id":426}}

... (creates a child process)

{"event":{"log":{"child":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}},"type":"fork"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":426,"ppid":1,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"args":["oahd-helper","3","4"],"cwd":{"path":"\/","path_truncated":false},"last_fd":4,"target":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}},"type":"exec"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

The oahd-helper takes two file descriptors (the x86_64 code and the AOT file to write to) as command-line arguments, translates x86_64 code into arm64 code, and saves the result as an AOT file.

When oahd-helper writes the result, it temporarily creates a file with the extension aot.in_progress and renames it to a file with the extension aot.

The reason for making the file aot.in_progress once is probably to avoid using the AOT file if the same application starts in the middle of writing the translated result.

... (oahd-helper writes the translated result)

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

{"event":{"log":{"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"write"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

... (closes file descriptor)

{"event":{"log":{"modified":true,"target":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"close"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd-helper","group_id":426,"pid":54133,"ppid":426,"session_id":426}}

... (renames)

{"event":{"log":{"destination_type":1,"dir":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0","path_truncated":false},"filename":"hello.out.aot","source":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot.in_progress","path_truncated":false}},"type":"rename"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Library\/Apple\/usr\/libexec\/oah\/oahd","group_id":426,"pid":426,"ppid":1,"session_id":426}}

Finally, this AOT file is mapped onto the memory of the hello.out process.

... (a segment of the AOT file is mapped onto the memory with PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC protection)

{"event":{"log":{"file_pos":0,"flags":131090,"max_protection":7,"protection":5,"source":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot","path_truncated":false}},"type":"mmap"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Users\/konakagawa.ffri\/hello.out","group_id":54132,"pid":54132,"ppid":48492,"session_id":48491}}

... (a segment of the AOT file is mapped onto the memory with PROT_READ protection)

{"event":{"log":{"file_pos":8192,"flags":18,"max_protection":7,"protection":1,"source":{"path":"\/private\/var\/db\/oah\/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00\/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0\/hello.out.aot","path_truncated":false}},"type":"mmap"},"target_process":{"executable_path":"\/Users\/konakagawa.ffri\/hello.out","group_id":54132,"pid":54132,"ppid":48492,"session_id":48491}}

You can see that PROT_EXEC protection is granted when looking at the first event of mmap.

From this, we can infer that the executable code is contained in the AOT file.

Next, let's dig into the AOT files.

Analyzing AOT files¶

Problems in analysis with Ghidra¶

First, let's check the file type.

$ file /var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0/hello.out.aot

/var/db/oah/16c6785d8fdab5ee2435f23dc2962ceda2e76042ea2ad1517687c5bb7358bf00/065b3f057e68a5474d378306e41d8b1e3e8e612b9cf9010b76449e02b607d7f0/hello.out.aot: Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64

file command says that the AOT file is just a Mach-O file, so it can be analyzed using the existing disassembler.

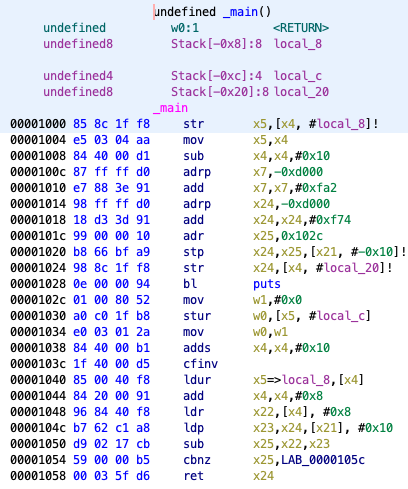

Let's import it with Ghidra version 9.2.1 (Figure 3).

We follow the symbol tree, go to the main function and show the disassembly listing (Figure 4) and the decompilation around main (Figure 5).

main function.main function.Unfortunately, there seems to be a problem with both the disassembly and decompilation.

The end of the main function is expected to be a branch instruction such as the ret instruction, but it is ended by the adds x4, x4, #0x10 instruction.

When you look at the decompilation, you can see that it ends at the function call halt_baddata(); with the comment "WARNING: Bad instruction - Truncating control flow here."

It seems that the disassembly was interrupted in the middle because it contains instructions that Ghidra does not support.

The instruction displayed as "Bad instruction" is cfinv instruction introduced in Armv8.4, which is not yet supported in Ghidra version 9.2.1.

You can see that in_* variables in the decompilation.

in_* is a variable seen when a read occurs before a write to a register that is not passed as an argument under the function's calling convention.

In general, if you see a lot of such variables in the decompilation of Ghidra, there is a high possibility that the calling convention specified at the decompiling time does not match the actual calling convention.

In this case, Ghidra decompiled the main function assuming the AArch64 ABI calling convention specified by default, but other proprietary calling conventions are likely being used.

We can proceed with the analysis, but why not modifying Ghidra? Ghidra is an OSS disassembler, which is designed to be easily customized by users.

The details will be presented later in a separate article. I solved these issues by fixing the SLEIGH file and the compiler specification (CSPEC) file. The patch is available from here.

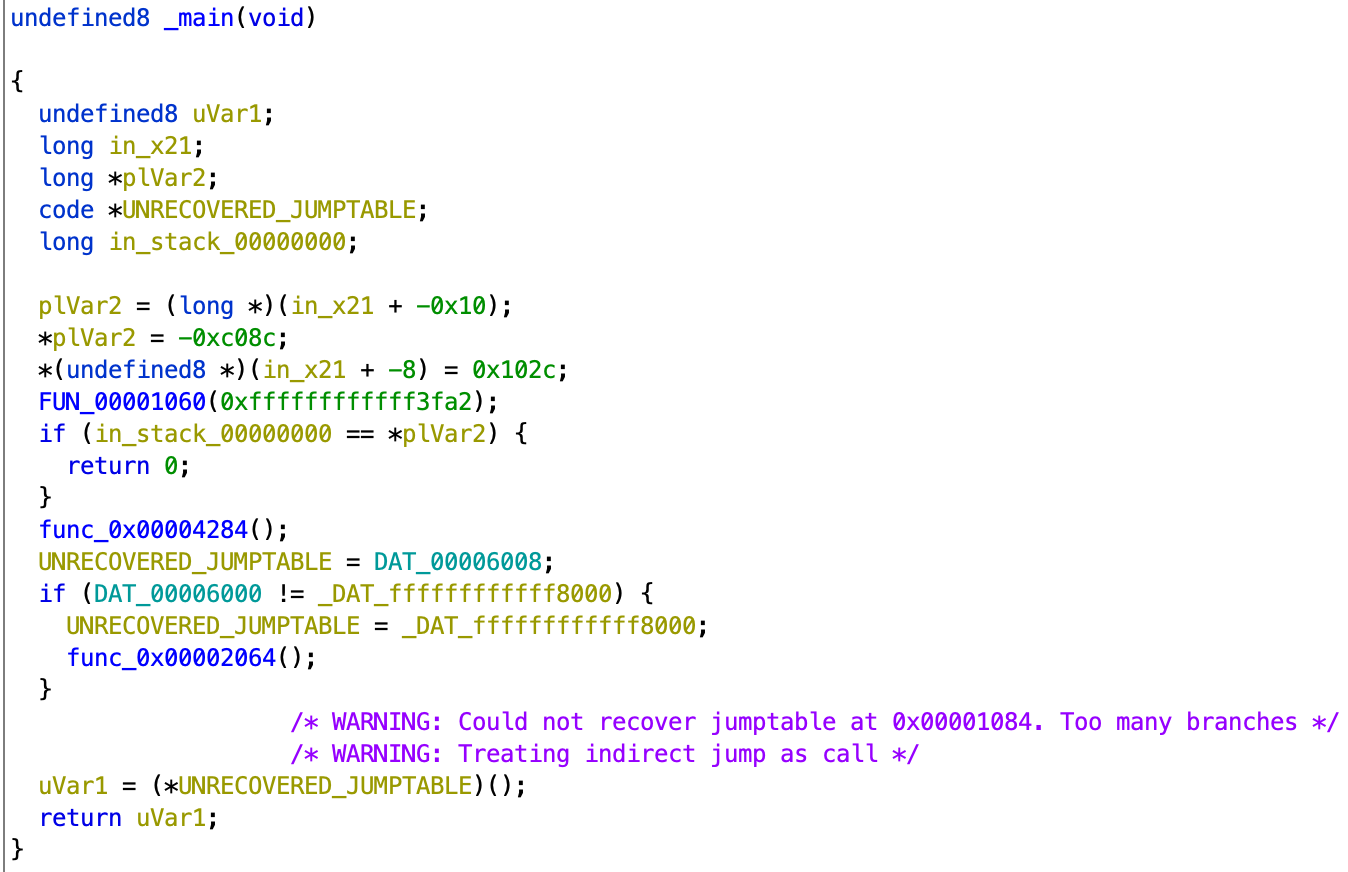

After fixing Ghidra, the entire main function can be disassembled and decompiled, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

main function after modifying Ghidra.

main function after modifying Ghidra.Analyzing the code in AOT files: calling conventions¶

Now that the analysis environment is in place, we can move on to the detailed analysis of the code contained in AOT files.

I mentioned earlier that a proprietary ABI is used in AOT files. Specifically, the System V AMD64 ABI is used, with the x86_64 registers converted to arm64 registers according to the following table.

| x86_64 | arm64 |

|---|---|

| RAX | x0 |

| RCX | x1 |

| RDX | x2 |

| RBX | x3 |

| RSP | x4 |

| RBP | x5 |

| RSI | x6 |

| RDI | x7 |

| R8 | x8 |

| R9 | x9 |

| R10 | x10 |

| R11 | x11 |

| R12 | x12 |

| R13 | x13 |

| R14 | x14 |

| R15 | x15 |

| XMM{0--15} | q{0--15} |

Let's look at an example to see the calling convention. The AOT file built from the following source code is used for the analysis.

#include <stdio.h>

__attribute__((noinline))

int int_arguments(int a1, int a2, int a3, int a4, int a5, int a6, int a7, int a8, int a9, int a10, int a11, int a12) {

return a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + a5 + a6 + a7 + a8 + a9 + a10 + a11 + a12;

}

__attribute__((noinline))

double double_arguments(double a1, double a2, double a3, double a4, double a5, double a6, double a7, double a8, double a9, double a10, double a11, double a12) {

return a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + a5 + a6 + a7 + a8 + a9 + a10 + a11 + a12;

}

int main() {

const int sum_int = int_arguments(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 2);

const double sum_double = double_arguments(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 2);

printf("%f %d\n", sum_double, sum_int);

}

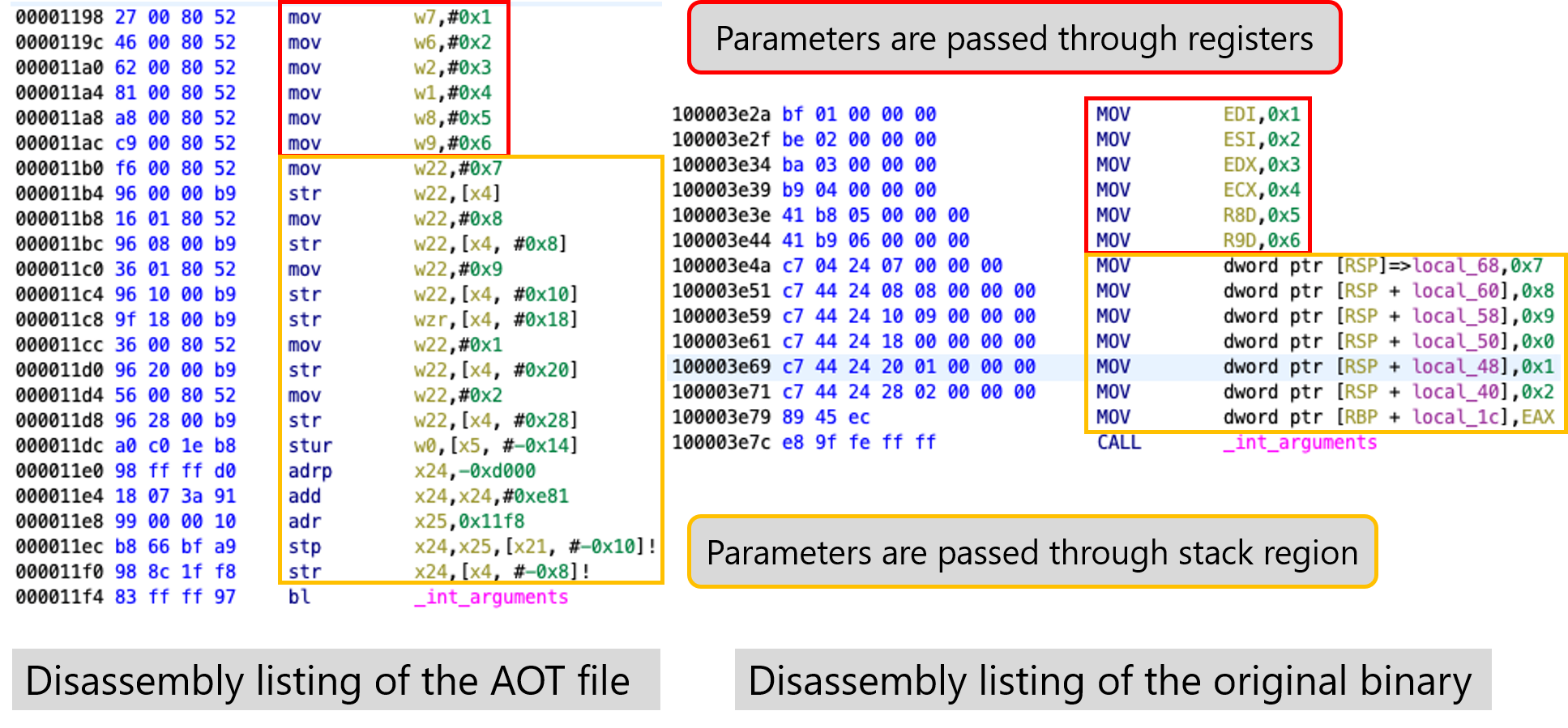

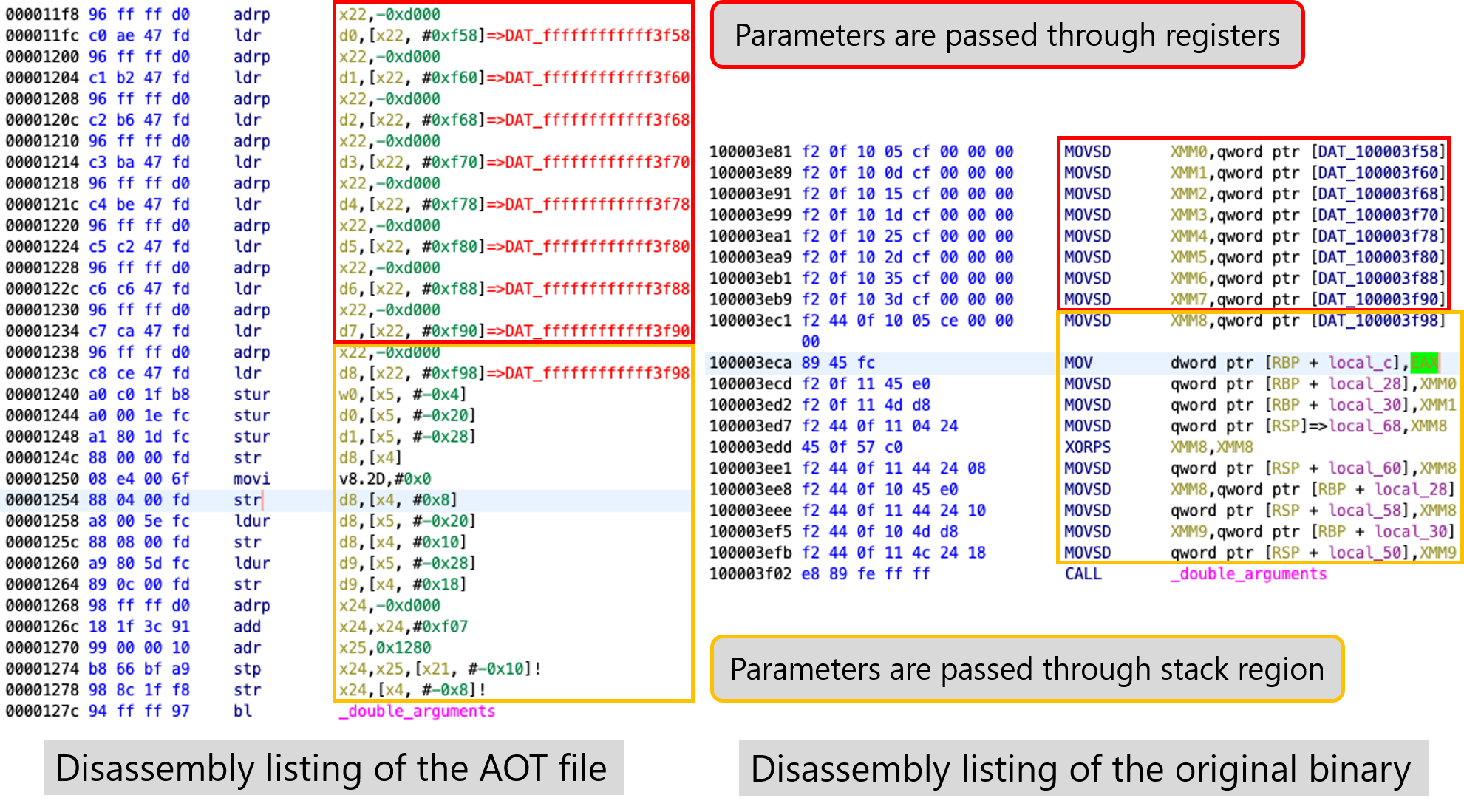

Here are the disassembly listings of the AOT file corresponding to the int_arguments (Figure 8) and double_arguments calls (Figure 9).

int_arguments.

double_arguments.According to the System V AMD64 ABI calling convention, integer and pointer values are passed through the RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9 registers. When there are more arguments, the additional arguments are passed through the stack. We check the corresponding registers of arm64 according to the table shown earlier. Consequently, we figure out that the arguments are passed through the x7, x6, x2, x1, x8, and x9 registers, and when there are more arguments, they are passed through the stack (note that x4 register specifies the top of the stack). You can easily understand that the left disassembly listing of Figure 8. follows such a calling convention.

In the same manner, you can understand the calling convention for float arguments (Figure 9).

Analyzing the code in AOT files: references to the x86_64 executable¶

When you analyze AOT files with Ghidra, you will see that several references do not exist in the program memory.

As shown in Figure 10, the DAT_ffffffffffff8000 and SUB_00002064 in red letters indicate that the reference does not exist in the program memory.

These occur because the references to the following two binaries do not exist in the Ghidra's program memory.

- The x86_64 binary that is the target of the emulation

- The Rosetta 2

runtimebinary that initializes the emulation process, maps the AOT file onto the memory, and performs JIT translation

In fact, these files are mapped onto the memory, and references to functions and variables are resolved correctly.

Let's check this by looking at the memory map of the emulation process using vmmap command.

==== Non-writable regions for process 70817

REGION TYPE START - END [ VSIZE RSDNT DIRTY SWAP] PRT/MAX SHRMOD PURGE REGION DETAIL

(__TEXT segment of x86_64 code)

__TEXT 100000000-100003000 [ 12K 12K 0K 0K] r-x/r-x SM=COW /Users/USER/Documents/*/check_calling_convention.out

__TEXT 100003000-100004000 [ 4K 4K 4K 0K] r-x/rwx SM=COW /Users/USER/Documents/*/check_calling_convention.out

__DATA_CONST 100004000-100008000 [ 16K 16K 16K 0K] r--/rw- SM=COW /Users/USER/Documents/*/check_calling_convention.out

__LINKEDIT 10000c000-10000d000 [ 4K 4K 0K 0K] r--/r-- SM=COW /Users/USER/Documents/*/check_calling_convention.out

__LINKEDIT 10000d000-100010000 [ 12K 0K 0K 0K] r--/r-- SM=NUL /Users/USER/Documents/*/check_calling_convention.out

(__TEXT segment of the AOT file)

mapped file 100010000-100012000 [ 8K 8K 0K 0K] r-x/rwx SM=COW /private/var/db/*/check_calling_convention.out.aot

(Rosetta 2 runtime)

mapped file 100012000-100016000 [ 16K 16K 0K 0K] r-x/r-x SM=COW /Library/Apple/*/runtime

(__LINKEDIT segment of the AOT file)

mapped file 100017000-100018000 [ 4K 4K 0K 0K] r--/rwx SM=COW /private/var/db/*/check_calling_convention.out.aot

(Rosetta 2 runtime)

mapped file 100020000-100024000 [ 16K 16K 0K 0K] r-x/r-x SM=COW /Library/Apple/*/runtime

Rosetta Thread Context 108023000-108024000 [ 4K 0K 0K 0K] ---/rwx SM=NUL

Rosetta Return Stack 108028000-108029000 [ 4K 0K 0K 0K] ---/rwx SM=NUL

...

You can see that the x86_64 executable and the runtime binary are mapped onto the areas before and after the AOT file, respectively.

So, in what cases do references to x86_64 or runtime from AOT files exist?

A typical case is when there is a reference to a global variable or constant in the x86_64 executable. Since the AOT file does not contain any constant data of the original x86_64 executable, it is necessary to reference it.

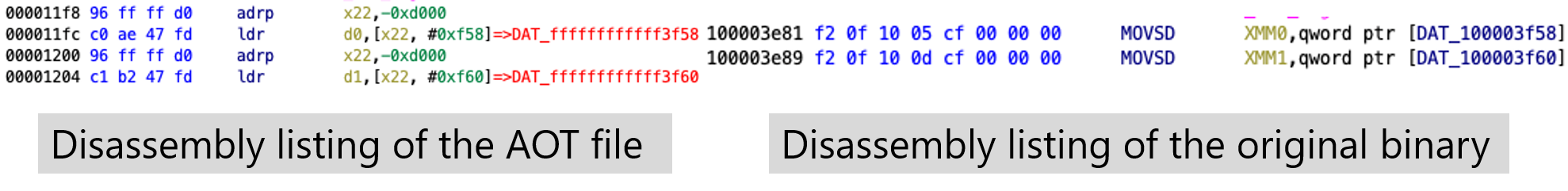

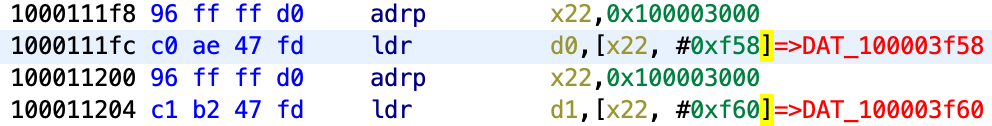

For example, take the code in Figure 9 shown earlier (the relevant part is only shown in Figure 11).

The MOVSD XMM0,DAT_100003f58 in the original x86_64 executable is translated into two instructions, adrp x22,-0xd00; ldr d0,[x22, #0xf58]; in the AOT file.

Currently, Ghidra maps the AOT file onto memory with a base address of 0x0 and displays the disassembly, but according to the command output of vmmap, the AOT file is mapped at 0x10001000.

So, let's change the base address to 0x100010000 where the AOT file is mapped, and reopen it.

You can see that it refers to DAT_100003f58 in the x86_64 code; that is, it refers to the constant data contained in the x86_64 executable from the AOT file.

Since there is no endianness change in this migration from x86_64 to arm64, there are no problems with simply adding references from the AOT file to the x86_64 code like this. However, in the past transition from PowerPC to Intel, the endianness change was required before referencing constants. Since changing the endianness at runtime has a large overhead, the AOT file probably also contained the data after the endianness was changed.

The cases where references to runtime exist will be discussed in the next section, along with explaining the reverse-engineering results of runtime.

Analyzing Rosetta 2 runtime¶

The Rosetta 2 runtime is the binary that initializes the emulation process, maps the AOT file onto the memory, and performs JIT translation.

When an x86_64 emulation process starts, runtime is mapped onto the memory, and the program counter is set to the entry point of runtime.

One interesting point is that runtime is not a dynamic link library.

This is in contrast to the x86 emulation engine xtajit.dll in Windows 10 on Arm.

In the case of xtajit.dll, it is loaded as a DLL from ntdll.dll via wow64.dll.

The currently known features of runtime are as follows.

- It resolves the address in an AOT file from the address of an x86_64 executable

- It performs the JIT binary translation from x86_64 code into arm64 code

- It checks the existence of an AOT file corresponding to an x86_64 executable

- It parses the header commands of an AOT file and maps it onto the memory

In this article, I will discuss the features of 1. and 2. The features of 3. and 4. will be covered in the next article.

X86_64 address resolution and lazy binding¶

Firstly, let's discuss the feature 1 by considering the AOT file of the following source code.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

puts("Hello World");

puts("Hello World Again");

puts("Hello World Again Again");

}

We follow the execution flow around puts function call in the AOT file of the above program.

Execution flow around puts function call in the AOT file¶

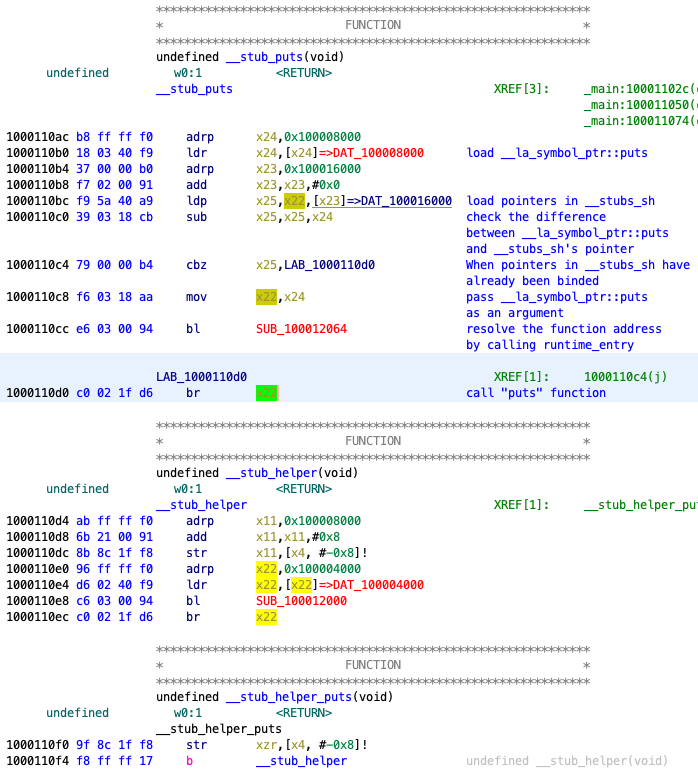

The disassembly listing near the puts function call in the AOT file is as follows (Figure 13).

Note that the base address is set to 0x100010000 when opening this file with Ghidra.

puts function call in the AOT file.First, it reads data from DAT_100008000 (the instruction at 0x1000110b0). DAT_100008000 contains the lazy symbol pointer (__la_symbol_ptr::puts) of puts function contained in the original x86_64 code.

Before the first puts function call, __la_symbol_pr::puts contains the function pointer to __stub_helper::puts.

Once the puts function is called, the dynamic linker overwrites the value of the __stub_helper::puts with the address of the puts function in libsystem_c.dylib.

(If you are not familiar with lazy binding, please refer to this page.)

Next, two 8-bytes pieces of data from the __stubs_sh section of the AOT file are loaded, and these values are assigned to x25 and x22 registers (the instruction at 0x1000110bc).

The __stubs_sh serves as a lazy symbol pointer in the AOT file.

That is, once the puts function is called, the contents of __stubs_sh are eventually overwritten with the address of the puts function by Rosetta 2 runtime.

After the binding, x25 and x22 are set to the x86_64 puts address and the AOT file's corresponding address, respectively.

So, what happens if the address of the puts function in __stubs_sh has not been resolved yet?

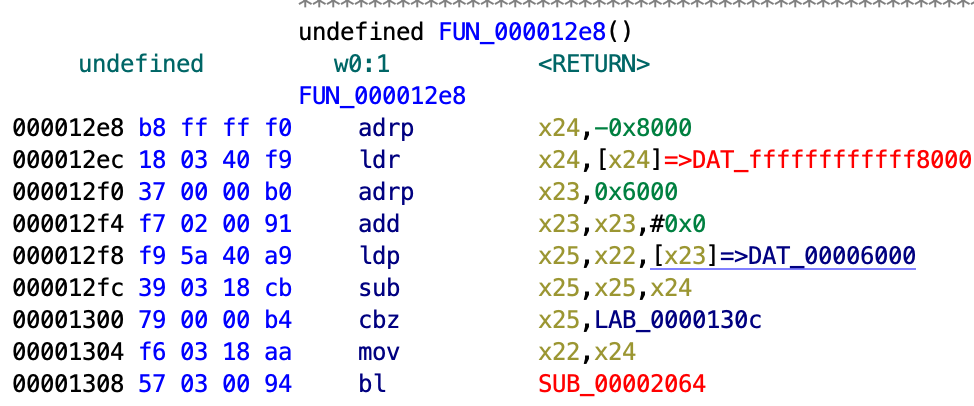

In this case, the address to be resolved is assigned to the x22 register (the instruction at 0x1000110c8), and then the SUB_100012064 function in runtime (the instruction at 0x1000110cc) is called to get the address in the corresponding AOT file.

Note that the result of the SUB_100012064 function call is stored in the x22 register.

Since the resolved address is stored in the x22 register, the puts function can be called at the br x22 instruction.

The SUB_100012064 function also reflects the resolved result in __stubs_sh.

Thus, the address of x86_64 passed to x22 register and the resolved address are stored in the __stubs_sh section.

In this way, the lazy binding mechanism is also employed in the AOT file, so the address is not resolved until the function is called.

In the following, we refer to the SUB_100012064 function as resolve_x64_addr.

Following the process of lazy binding in the AOT file.¶

Let's follow the process of lazy binding in the AOT file with LLDB.

Put a breakpoint and check the pointer values in __la_symbol_ptr::puts and __stubs_sh before calling the puts function.

Before the first call to the puts function

# reads the data in __la_symbol::puts

# 0x0000000100003f6c corresponds to the address of __stub_helper::_puts

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100008000 -c 1 -s 8

0x100008000: {0x0000000100003f6c}

# reads the data in __stubs_sh

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100016000 -c 1 -s 16

0x100016000: {0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000}

You can see that __stubs_sh contains a value of 0 and __la_symbol::puts contains the pointer to __stub_helper::puts.

Before the second call to the puts function

# reads the data in __la_symbol::puts

# __la_symbol::puts is modified to 0x00007fff20324274 (the function address of puts in libsystem_c.dylib) by dynamic linker

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100008000 -c 1 -s 8

0x100008000: {0x00007fff20324274}

# reads the data in __stubs_sh

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100016000 -c 1 -s 16

0x100016000: {0x0000000100003f6c 0x00000001000110f0}

Once the puts function is called, you see that the contents of __la_symbol::puts are overwritten and changed to 0x00007fff20324274, which is the address of the puts function in libsystem_c.dylib.

This means that the first call to puts causes the dynamic linker to change the contents of __la_symbol_ptr::puts to point directly to the address of the puts function.

On the other hand, you can see that __stubs_sh has been written to {0x0000000100003f6c 0x0000000110f0}.

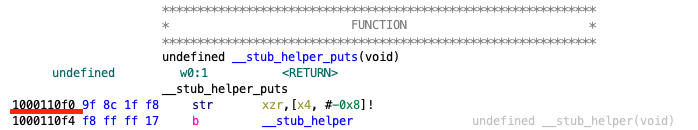

These addresses correspond to the addresses in the x86_64 executable and the AOT file of __stub_helper::puts, respectively (see Figure 14).

This is because the resolve_x64_addr function was called with the function pointer of __stub_helper::_puts in x86_64 code as an argument at the first call.

puts in the AOT file.Before the third call to the puts function

# reads the data in __la_symbol::puts

# __la_symbol::puts is modified to 0x00007fff20324274 (puts function address of libsystem_c.dylib) by dynamic linker

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100008000 -c 1 -s 8

0x100008000: {0x00007fff20324274}

# reads the data in __stubs_sh

(lldb) memory read -f uint64_t[] -a 0x0000000100016000 -c 1 -s 16

0x100016000: {0x00007fff20324274 0x00007ffe9664644c}

There is no change in the contents of __la_symbol::puts.

On the contrary, you can see that __stubs_sh has been rewritten as {0x00007fff20324274, 0x00007ffe9664644c}.

This is because the resolve_x64_addr function was called with the address of the puts in libsystem_c.dylib as an argument at the second call.

You can see that the resolved address is stored in __stubs_sh.

In summary, the contents of __stubs_sh are updated as follows.

- Before the first

putsfunction call: {0, 0} - Before the second

putsfunction call: {__stubs_helper::putsfunction address,__stubs_helper::putsaddress in the corresponding AOT file} - Before the third call to the

putsfunction: {address of theputsfunction inlibsystem_c.dylib, address in the corresponding AOT file}

After the second call to the puts function, the puts function is directly called without calling Rosetta 2 runtime's resolve_x64_addr.

resolve_x64_addr internal¶

Next, let's focus on the analysis of resolve_x64_addr function.

When resolve_x64_addr is called, the currently running context is saved (Figure 15).

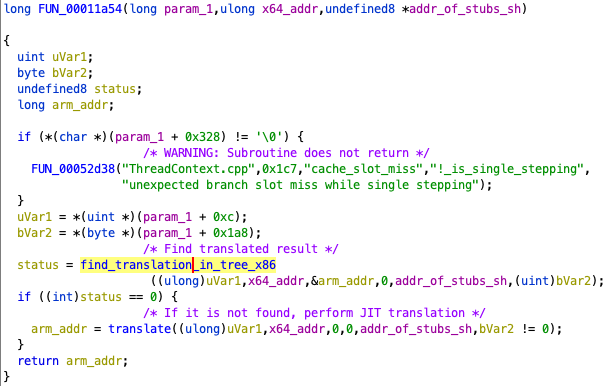

Then, FUN_00011a54 (0x00011a54+runtime) is called.

The FUN_00011a54 function takes the address of the x86_64 to be resolved as the second argument, and the address to __stubs_sh as the third argument (Figure 16).

In the first call to the find_translation_in_tree_x86 (0x00022070+runtime) in the FUN_00011a54, the corresponding AOT file's address will be searched.

This search is done against the red-black tree that holds the correspondence between the x86_64 executable and the AOT file address.

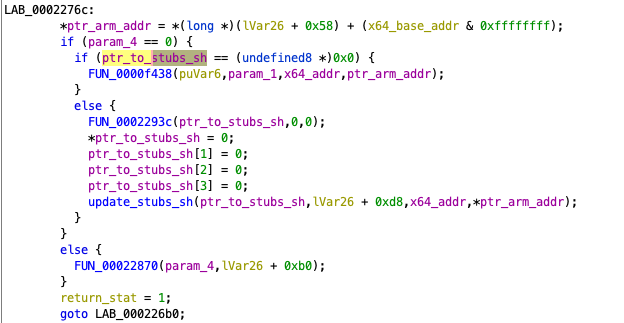

If found, find_translation_in_tree_x86 updates the contents of __stubs_sh, and stores the found address of the AOT file (Figure 17) to the address specified as the third argument.

find_translation_in_tree_x86 updating the content of __stubs_sh.If not found, find_translation_in_tree_x86 returns 0. In this case, translate (0x00028954+runtime) function is called in the FUN_00011a54 function (Figure 16).

The translate function, which will be explained in detail in the next section, translates x86_64 code into arm64 code in JIT and returning the result.

The translate function is probably called when calling a function in a shared library that does not have an AOT file at the time of execution.

Finally, resolve_x64_addr assigns the return value to x22, and goes back to the AOT file.

JIT binary translation of Rosetta 2 runtime: translate function¶

I mentioned the translate function at the end of the previous section.

Rosetta 2 implements the logic for JIT code translation as well as AOT code translation.

The logic for JIT translation is also needed is to support the execution of x86_64 applications that generate x86_64 code at runtime (e.g., JavaScript engine uses a JIT compiler).

For this kind of application, AOT translation is not enough because a portion of machine code to be executed is determined only at runtime. In order to execute such an application, the x86_64 code generated at runtime must be translated into arm64 by the JIT translator.

Rosetta 2 runtime is able to translate the x86_64 machine code in a heap to arm64 and then execute it.

In this section, we will look at the JIT translation feature included in Rosetta 2 runtime.

Target application¶

Let's follow the process of JIT translation in Rosetta 2 runtime through the following source code example.

// run_shellcode.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

typedef int (*sc)();

char shellcode[] =

"\x48\x31\xc0\x99\x50\x48\xbf\x2f\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x57\x54\x5f\x48\x31\xf6\xb0\x02\x48\xc1\xc8\x28\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05";

/*

section .text

global start

start:

; execve("//bin/sh", 0, 0)

xor rax, rax

cdq

push rax

mov rdi, 0x68732f6e69622f2f

push rdi

push rsp

pop rdi

xor rsi, rsi

mov al, 0x2

ror rax, 0x28

mov al, 0x3b

syscall

*/

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

void *ptr = mmap(0, 0x22, PROT_EXEC | PROT_WRITE | PROT_READ, MAP_ANON | MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0);

if (ptr == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap");

exit(-1);

}

memcpy(ptr, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

((sc)ptr)(); // <----- run shellcode

return 0;

}

The above code is a modified version of OSX/x86_64 - execve(/bin/sh) + Null-Free Shellcode (34 bytes). The process is as follows:

- Allocate a memory region with W+R+X permission by anonymous mapping

- Write

shellcode - Go to the heap region where the

shellcodeis written

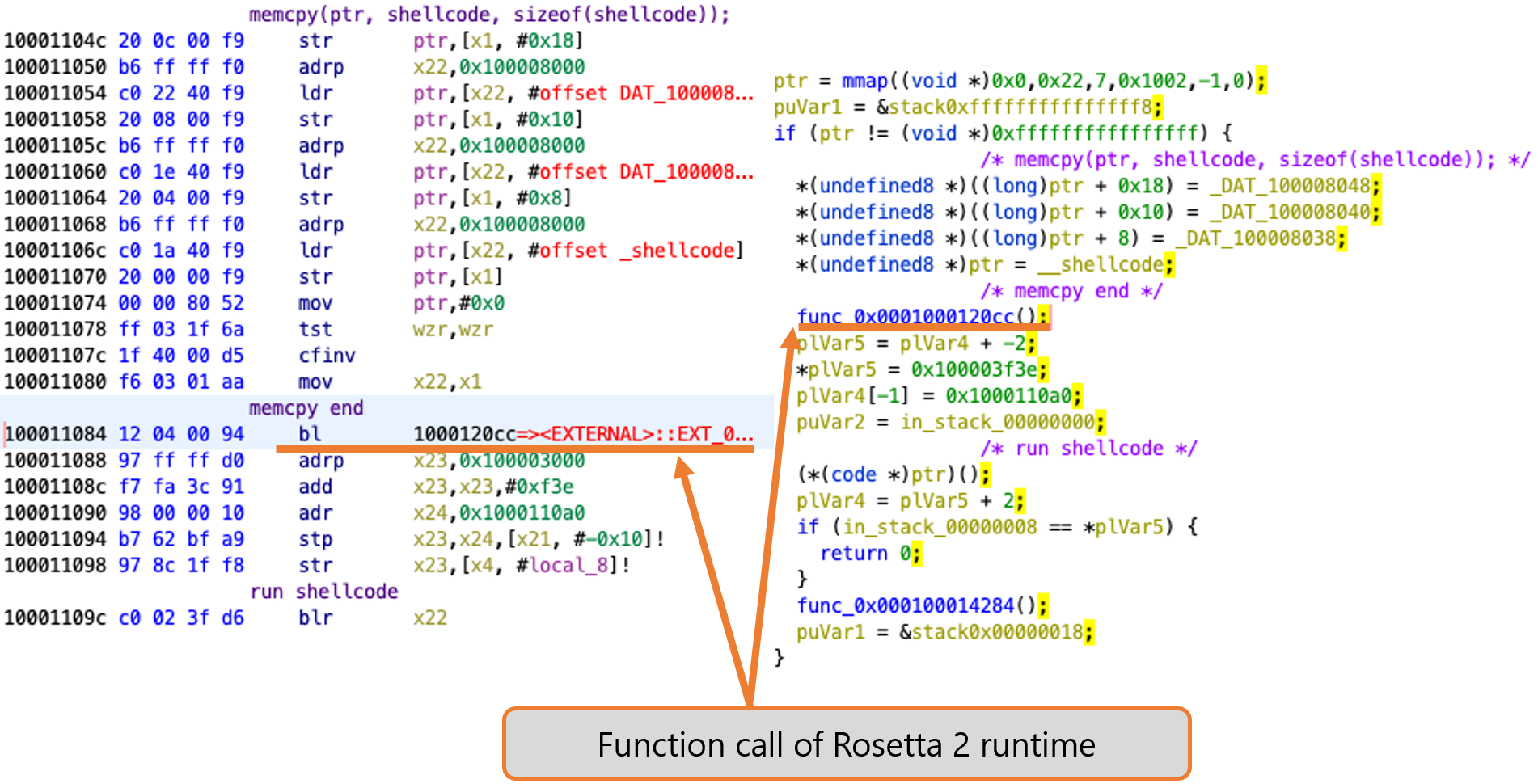

Here, I show the disassembly listing and the decompilation of the AOT file corresponding to the above x86_64 code (Figure 18). Note that the base address is set to 0x100010000.

You notice that the call to the func_0x0001000120cc function exists between memcpy and the execution of the shellcode.

func_0x0001000120cc in Rosetta 2 runtime is called after passing the address of the shellcode to x22.

The func_0x0001000120cc function saves the currently running context and then calls the translate_indirect_branch (runtime+0x11944) function to translate the x86_64 shellcode to arm64 one.

After exiting the function, x22 will contain the pointer to the region that includes the JIT translated code.

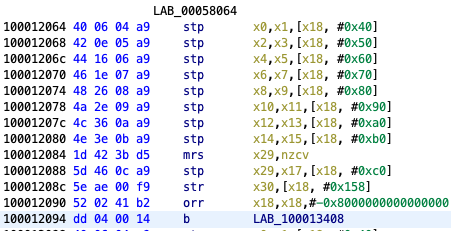

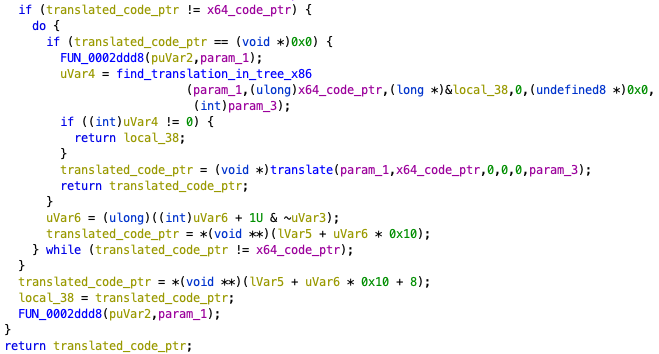

In the translate_indirect_branch function, FUN_00022ac0 (runtime+0x22ac0) is called, and two more functions are called in it: the translate function and the find_translation_in_tree_x86 function (Figure 19).

These two functions have already been introduced in resolve_x64_addr internal.

The FUN_00022ac0 function also first searches for results that have already been translated by the translate_indirect_branch function, and performs JIT translation only if there is none.

FUN_00022ac0.Analyzing the x86_64 machine code decoding process¶

Not surprisingly, the translate function is large, and the number of functions called in it is huge.

For example, the following functions are called

- The

decode_opcode(runtime+0x55e6c) function used to parse the opcode of the x86_64 machine code - The

decode_operand_mem16(runtime+0x56ab0) function is used to parse the operand of the x86_64 machine code

This section delves into the process found in the first part of the decode_opcode function used for parsing opcodes.

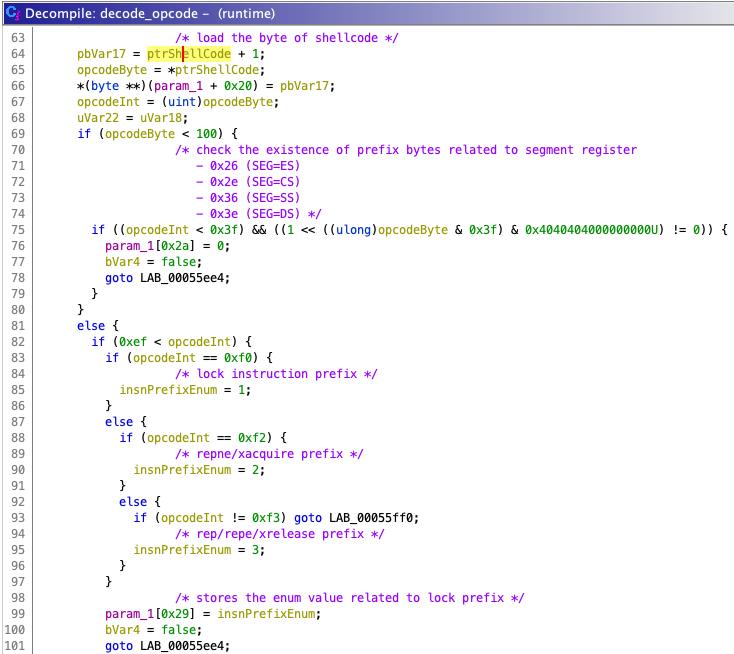

The following is a portion of the decompilation of decode_opcode, starting with checking the x86_64 prefix byte.

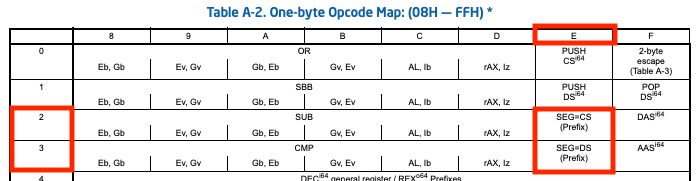

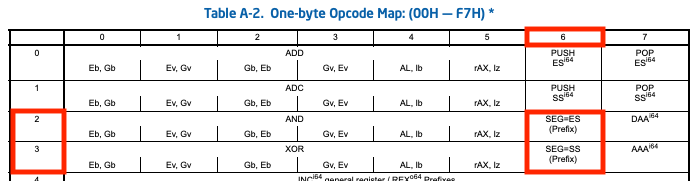

decode_opcode function.You can see the conditional expression ((opcodeInt < 0x3f) && ((1 << opcodeBytes 0x3f) & 0x4040404000000000) != 0), which is equivalent to (opcodeInt == 0x26) | (opcodeInt == 0x2e) | (opcodeInt == 0x36) | (opcodeInt == 0x3e). What are those magic numbers (0x26, 0x2e, 0x36, 0x3e)?

According to the Intel 64 and IA-32 Architecture software developer's manual Volume 2D: Instruction set reference Table A-2, these opcodes mean the segment override prefixes, which are used for overwriting the default segment settings (Figure 21 and Figure 22).

You can also see the process of checking the lock prefix (0xf0), repne/repnz prefix (0xf2), rep/repe/repz prefix (0xf3).

The result of checking the prefix byte is assigned to the structure specified by the first argument of decode_opcode (corresponds to the param_1 variable in Figure 20).

The prefix bytes seem to be assigned to a separate field for each group, as shown here.

Conclusion¶

In this article, I have reported on the following aspects of Rosetta 2.

- How

oahdexecutesoahd-helperand creates the AOT file after starting the x86_64 process - Results of the static analysis of the AOT file

- Calling conventions used in the AOT file

- The two features of

runtime- Lazy binding of AOT files

- JIT binary translation from x86_64 to arm64

Rosetta 2 was reported to have a good score in Geekbench 5, so its design seems sophisticated. We hope that this article will lead to further analysis of Rosetta 2 and reveal its sophisticated design.

What's next?¶

The following points will be introduced in part2 and beyond. I will publish these results in a few weeks.

- Other features of Rosetta 2

runtime- Loading of AOT files

- The ability to query

oahdfor the existence of AOT files via Mach IPC

- Debug modes included in Rosetta 2

runtime- Tracing of JIT translations (

ROSETTA_PRINT_IR) - Printing the information on segments mapped onto the memory (

ROSETTA_PRINT_SEGMENTS)

- Tracing of JIT translations (

LC_AOT_METADATAload command included in an AOT file- Speeding up the loading process with AOT shared cache files

- Introduction to the AOT shared cache file structure and the parser

- The parser of AOT shared cache files is available here.

- Code signatures included in AOT files and AOT shared cache files

- How to debug the x86_64 emulation process at the arm64 instruction level

- How to create a patch to parse an AOT file with Ghidra